Lalibela, a small city of approximately 15,000 people located in the Wollo Province of the Amhara Region of Northern Ethiopia, is considered one of the nation’s holiest cities and is the destination for pilgrimages by Ethiopian Orthodox Christians from around the nation. It was envisioned to be a “New Jerusalem” in response to the capture of Jerusalem by the Muslims in 1187. Originally called Roha, the town took the name of Gebra Maskal Lalibela, the Emperor of Ethiopia from 1185 to 1225 and one of the last rulers of the Zagwe Dynasty.

According to local history Lalibela, who had visited Jerusalem before its conquest, vowed after its fall to make Roha his new capital and to ensure that it would recall the glory of old Jerusalem. He gave biblical names to many of the town’s features and encouraged architecture that followed established Christian themes. Lalibela remained the capital of Ethiopia for more than a century after the Emperor’s death.

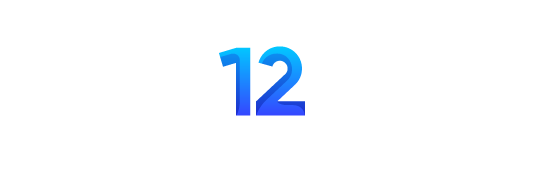

It is a religious and pilgrimage centre in North-Central Ethiopia. Roha, capital of the Zagwe dynasty for about 300 years, was renamed for its most distinguished monarch, Lalībela (late 12th–early 13th century), who, according to tradition, built the 11 monolithic churches for which the place is famous. The churches were hewn out of solid rock (entirely below ground level) in a variety of styles. Generally, trenches were excavated in a rectangle, isolating a solid granite block. The block was then carved both externally and internally, the work proceeding from the top downward.

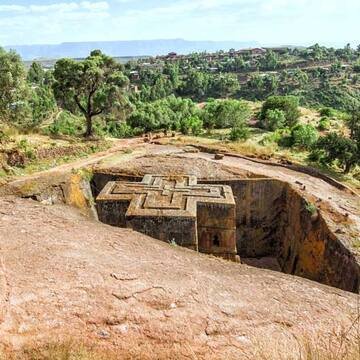

The churches are arranged in two main groups, connected by subterranean passageways. One group, surrounded by a trench 36 feet (11 metres) deep, includes House of Emmanuel, House of Mercurios, Abba Libanos, and House of Gabriel, all carved from a single rock hill. House of Medhane Alem (“Saviour of the World”) is the largest church, 109 feet (33 metres) long, 77 feet (23 metres) wide, and 35 feet (10 metres) deep. House of Giyorgis, cruciform in shape, is carved from a sloping rock terrace. House of Golgotha contains Lalībela’s tomb, and House of Mariam is noted for its frescoes. The interiors were hollowed out into naves and given vaulted ceilings.

The expert craftsmanship of the Lalībela churches has been linked with the earlier church of Debre Damo near Aksum and tends to support the assumption of a well-developed Ethiopian tradition of architecture. Emperor Lalībela had most of the churches constructed in his capital, Roha, in the hope of replacing ancient Aksum as a city of Ethiopian preeminence. Restoration work in the 20th century indicated that some of the churches may have been used originally as fortifications and royal residences.

The churches attract thousands of pilgrims during the major holy day celebrations and are tended by priests of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. The town also serves as a market centre for the Amhara people.

About the Ethiopian Orthodox church

Tradition holds that Ethiopia was first evangelized by St. Matthew and St. Bartholomew in the 1st century CE, and the first Ethiopian convert is thought to have been the eunuch in Jerusalem mentioned in The Acts of the Apostles (8:27–40). Ethiopia was further Christianized in the 4th century CE by two men (likely brothers) from Tyre — St. Frumentius, later consecrated the first Ethiopian bishop, and Aedesius. They won the confidence of the king at Aksum (a powerful kingdom in northern Ethiopia) and were allowed to evangelize. The succeeding king, Ezana, was baptized by Frumentius, and Christianity was made the state religion. Toward the end of the 5th century, nine monks from Syria are said to have brought monasticism to Ethiopia and encouraged the translation of the Scriptures into the Geʿez language.

The Ethiopian church followed the Coptic (Egyptian) church (now called the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria) in rejecting the Christological decision issued by the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE that the human and divine natures of Jesus Christ were equally present in one person without commingling. Opposed to this dyophysitism, or two-nature doctrine, the Coptic and Ethiopian churches held that the human and divine natures were equally present through the mystery of the Incarnation within a single nature. This position—called miaphysitism, or single-nature doctrine—was interpreted by the Roman and Greek churches as a heresy called monophysitism, the belief that Christ had only one nature, which was divine. The Ethiopian church included into its name the word tewahedo, a Geʿez word meaning “unity” and expressing the church’s miaphysite belief. Like other so-called non-Chalcedonian (also referred to as Oriental Orthodox) churches, it was cut off from dialogue with the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches until the mid-20th century, when many of the Christological disputes that arose from Chalcedon were resolved through ecumenical dialogue.

In the 7th century the conquests of the Muslim Arabs cut off the Ethiopian church from contact with most of its Christian neighbours. The church absorbed various syncretic beliefs in the following centuries, but contact with the outside Christian world was maintained through the Ethiopian monastery in Jerusalem.

Beginning in the 12th century, the patriarch of Alexandria appointed the Ethiopian archbishop, known as the abuna (Arabic: “our father”), who was always an Egyptian Coptic monk; this created a rivalry with the native itshage (abbot general) of the strong Ethiopian monastic community. Attempts to shake Egyptian Coptic control were made from time to time, but it was not until 1929 that a compromise was effected: an Egyptian monk was again appointed abuna, but four Ethiopian bishops were also consecrated as his auxiliaries. A native Ethiopian abuna, Basil, was finally appointed in 1950, and in 1959 an autonomous Ethiopian patriarchate was established, although the church continued to recognize the honorary primacy of the Coptic patriarch. When neighbouring Eritrea gained independence from Ethiopia in 1993, it appealed to Pope Shenouda III, the patriarch of the Coptic church, for autocephaly. This was granted in 1994; the Ethiopian church assented in 1998 to the independence of the new Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

The Amhara and Tigray peoples of the northern and central highlands have historically been the principal adherents of the Ethiopian Orthodox church, and the church’s religious forms and beliefs have been the dominant element in Amhara culture. Under the Amhara-dominated Ethiopian monarchy, the Ethiopian Orthodox church was declared to be the state church of the country, and it was a bulwark of the regime of Emperor Haile Selassie I. Upon the abolition of the monarchy and the institution of socialism in the country beginning in 1974, the church was disestablished. Its patriarch was executed, and the church was divested of its extensive landholdings. The church was placed on a footing of equality with Islam and other religions in the country, but it nevertheless remained Ethiopia’s most influential religious body.

The clergy is composed of priests, who conduct the religious services and perform exorcisms; deacons, who assist in the services; and ‘debtera’, who, though not ordained, perform the music and dance associated with church services and also function as astrologers, fortune-tellers, and healers. Ethiopian Christianity blends Christian conceptions of saints and angels with pre-Christian beliefs in benevolent and malevolent spirits and imps. Considerable emphasis is placed on the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament). Further, the church recognizes a wider canon of scripture that includes such texts as the apocalyptic First Book of Enoch. Circumcision is almost universally practiced; the Saturday Sabbath (in addition to Sunday) is observed by some devout believers; the ark is an essential item in every church; and rigorous fasting is still practiced.

The priesthood of the Ethiopian church, on the whole, is not learned, though there are theological seminaries in Addis Ababa and Harer. Monasticism is widespread, and individual monasteries often teach special subjects in theology or church music. Each community also has its own church school, which until 1900 was the sole source of Ethiopian education. The liturgy and scriptures are typically in Geʿez, though both have been translated into Amharic, the principal modern language of Ethiopia. In the early 21st century the church claimed more than 30 million adherents in Ethiopia.

Thirteen unusual churches were built in and around Lalibela. Each church sits below ground level and was cut directly into the rocky terrain. These church buildings are architectural marvels. The floors, columns, windows, doors and even roofs were constructed by carving into enormous pieces of solid rock. Some of these structures are “pure” monolithic churches, meaning the entire edifice is carved from a single rock with only the floor still connected to the terrain. Four of the twelve rock-cut churches are “pure” monolithic churches, Bete Madhane Alam, Bete Maryam, Bete Amanu’el, and Bete Giyorgis, the most finely built and best preserved of the churches.

Abba Libanos, another full rock-cut church, is unique in that it has walkways surrounding the outside of the building. These walkways connect to the landscape at the top of the structure. Bete Madhane Alam, the largest church, houses the Lalibela Cross. Bete Golgotha, known for the art on its walls, is said to contain the tomb of Emperor Lalibela.

Some historians theorize that not all of the thirteen buildings were intended to be churches. Bete Gabriel-Rufael was possibly a royal palace and Bete Merkorios may have been a former prison.

Complementing all of these rock-cut churches is an extensive system of drains, defense trenches, and ceremonial passages all cut out of the volcanic rock common to the region.

There is scholarly debate regarding when and how and why these churches were constructed because of the differing architectural and engineering styles. This debate is ongoing and carbon-14 data has been inconclusive. Nonetheless because of its churches, Lalibela is a World Heritage Site and thousands of tourists mix with Christian Pilgrims to visit the town and its churches each year.

Whenever you plan your trip to Africa, include a visit to Lalibela in Ethiopia to your bucket list. You could not only experience the beauty of it, or maybe even get your breakthrough from there…