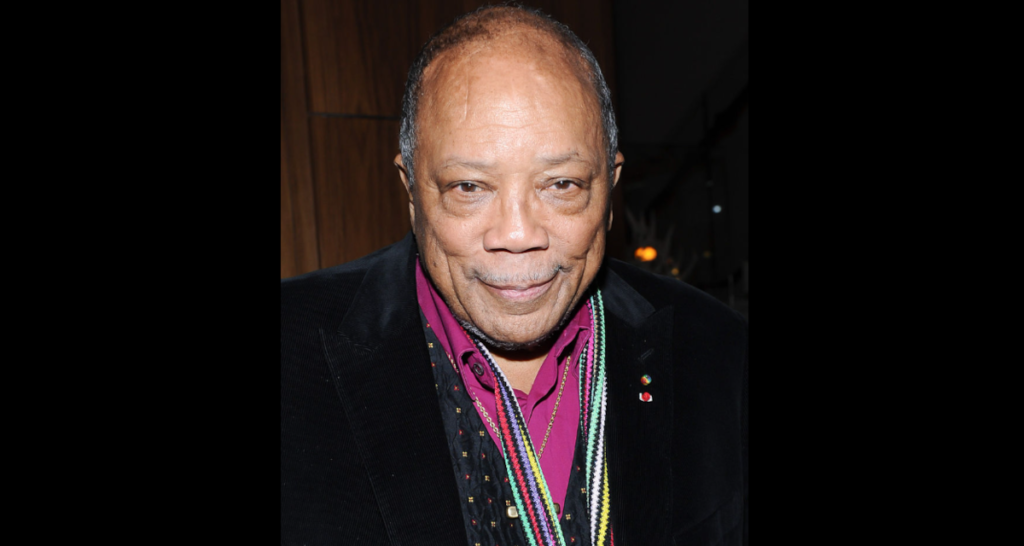

The publicist of the Global icon said he passed away on Sunday night at his home in Bel Air, Los Angeles, surrounded by his family.

Quincy Jones, one of the most powerful forces in American popular music for more than half a century, died on Sunday night in his home in the Bel Air section of Los Angeles. He was 91. His death was confirmed in a statement by his publicist, Arnold Robinson, who did not specify the cause.

Quincy Delight Jones Jr. was an American record producer, songwriter, composer, arranger, and film and television producer. Over the course of his career, he received several accolades including 28 Grammy Awards, a Primetime Emmy Award and a Tony Award as well as nominations for seven Academy Awards and four Golden Globe Awards.

Quincy Delight Jones Jr. was born in the South Side of Chicago on March 14, 1933, the elder of two sons to Sara Frances (née Wells; 1904–1999, a bank officer and apartment complex manager, and Quincy Delight Jones (1895–1971), a semi-professional baseball player and carpenter from Charleston, South Carolina. Quincy Jr.’s paternal grandmother was an ex-slave from Louisville, and he later discovered that his paternal grandfather was Welsh.

According to his publicist, Mr. Jones is survived by a brother, Richard; two sisters, Margie Jay and Theresa Frank; and seven children: Jolie, Kidada, Kenya, Martina, Rachel, Rashida and Quincy III.

Jones’ grandmother was born there on a plantation in Kentucky. He traced this all the way back to the Laniers, the same family as Tennessee Williams.” Learning that the Lanier immigrant ancestors were French Huguenots who had court musicians among their ancestors, Jones attributed some of his musicianship to them.

In his final decades, Mr. Jones dedicated much of his time to charity work through his Listen Up! Foundation; established a Quincy Jones professorship of African American music at Harvard University; produced “Keep On Keepin’ On,” a 2014 film about the teacher-student relationship between the 89-year-old Clark Terry, Mr. Jones’s old mentor, and Justin Kauflin, a young blind jazz pianist; and released the album “Soul Bossa Nostra,” reprising songs he’d produced in the past, with appearances by Snoop Dogg, T-Pain and Amy Winehouse, who contributed a louche version of “It’s My Party” — her last commercial release before her death in 2011.

Born in Chicago in 1933, Jones was brought up in Seattle. He began learning the trumpet as a teenager. He moved to New York City in the early 1950s, finding work as an arranger and musician with Count Basie, Tommy Dorsey, and Lionel Hampton. In 1956, Dizzy Gillespie chose Jones to play in his big band, later having him put together a band and act as musical director on Gillespie’s U.S. State Department tours of South America and the Middle East. The experience honed Jones’ skills at leading a jazz orchestra. Jones moved to Paris, France, in 1957, and studied music theory with the renowned Nadia Boulanger, and he put together a jazz orchestra that toured throughout Europe and North America. Though critically acclaimed, the tour did not make money, and Jones disbanded the orchestra. Jones would cite the hymns his mother sang around the house as the first music he could remember. He rose from running with gangs on the South Side of Chicago to the very heights of show business, becoming one of the first Black executives to thrive in Hollywood.

Jones leaves a vast legacy that ranged from producing Michael Jackson’s historic “Thriller” album to writing prize-winning film and television scores.

The musician and producer also collaborated with Frank Sinatra, Ray Charles among hundreds of recording artists.

Quincy Jones distinguished himself in nearly every aspect of music, including as a bandleader, record producer, musical composer and arranger, trumpeter, and record label executive. He worked with everyone from Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, and Count Basie to Frank Sinatra, Aretha Franklin, and Michael Jackson.

The list of his honours and awards filled 18 pages in his 2001 autobiography “Q”.”

Jones kept company with presidents and foreign leaders, movie stars and musicians, philanthropists and business leaders. He is seen in in 1996 with Nelson Mandela at a charity concert at The Royal Albert Hall in London.

Mr. Jones began his career as a jazz trumpeter and was later in great demand as an arranger, writing for the big bands of Count Basie and others; as a composer of film music; and as a record producer. But he may have made his most lasting mark by doing what some believe to be equally important in the ground-level history of an art form: the work of connecting.

Beyond his hands-on work with score paper, he organized, charmed, persuaded, hired and validated. Starting in the late 1950s, he took social and professional mobility to a new level in Black popular art, eventually creating the conditions for a great deal of music to flow between styles, outlets and markets. And all of that could be said of him even if he had not produced Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” the best-selling album of all time.

Mr. Jones stayed in the public eye. In 2018, he made headlines when he gave wide-ranging interviews to New York and GQ magazines that contained surprising comments about Michael Jackson and other subjects.

But even his not-fully-realized back-burner projects tell a story of their own, a kind of secondary biography of the obsessions and connections of a constantly busy man. Among them were a musical about Sammy Davis Jr.; a Cirque du Soleil show on the history of Black American music, from its African roots; a film about Brazilian carnivals; a film version of Ralph Ellison’s unfinished novel “Juneteenth”; and a film on the life of Alexander Pushkin, the Russian poet who was said to be of African origin.

In addition to his film scoring, he also continued to produce and arrange sessions in the 1960s, notably for Frank Sinatra on his albums with Count Basie, It Might As Well Be Swing in 1964 and Sinatra at the Sands in 1966. He later produced Sinatra’s L.A. Is My Lady album in 1984.

Returning to the studio with his own work, he recorded a series of Grammy Award-winning albums between 1969 and 1981, including Walking in Space and You’ve Got It Bad, Girl. Following recovery from a near-fatal cerebral aneurysm in 1974, he focused on producing albums, most successfully with Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall and Thriller, and the “We Are the World” sessions to raise money for the victims of Ethiopia’s famine in 1985. In 1991, he coaxed Miles Davis into revisiting his 1950s orchestral collaborations with Gil Evans at the Montreux Jazz Festival, conducting the orchestra for Davis’ last concert. Jones holds the record for the most Grammy Award nominations at 80, of which he won 28. Jones was awarded the National Medal of Arts, the highest honor given to artists and arts patrons by the United States government, in 2010 by President Obama.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Jones ventured into filmmaking, co-producing with Steven Spielberg “The Color Purple”, and managing his own record label Qwest Records, along with continuing to make and produce music.