‘It has the smell of the oasis’: how palm husks became prize-winning Moroccan art

Female weavers in a Berber-speaking village helped Amina Agueznay to create a work that won the Norval Sovereign African art prize

Meet Amina Agueznay, who trained and practiced as an architect before turning to art. And she says: ‘I can’t hug my buildings, but I can hug my artwork.’

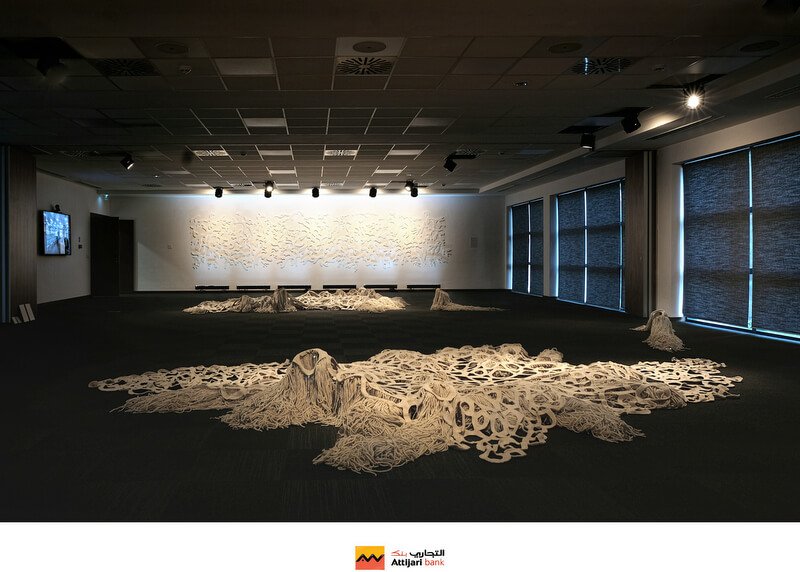

The idea of weaving an artwork from palm husks came to Amina Agueznay during a workshop she was leading in Morocco’s Souss-Massa region, as part of a project with local rug weavers to renovate Tissekmoudine, a ksar, or fortified village.

“The plan was to integrate the palm trees from the oasis in our designs, so I encouraged the women to look around them and use whatever material they could find,” says Agueznay, who this month won the Norval Sovereign African art prize, worth $35,000 (£28,000).

“We decided to weave with what, in the Berber language, the women call talefdamt [palm husk],” Agueznay recalls. “We deconstructed it to create a thread that we could use.”

This prize is an encouragement … empowering women that I work with.

The architect turned artist, who is known for collaborating with rural craftworkers and documenting their designs and traditions, says she feels “blessed” by the win.

“This prize is an encouragement and the will to continue, empowering women that I work with. I lead workshops throughout Morocco and what happens is that I always go back. There is a continuity, and continuity is very important to me – what we call la pérennité [sustainability].

For Amina Agueznay, a Casablanca-based artist, jewellery designer and architect, creativity and art are part of her DNA. She grew up in a household immersed in creative expression and freedom, surrounded by her artist mother and her fellow Casablanca School artist-friends.

“My mother encouraged all kinds of artistic expression. We even had a darkroom, which was uncommon. It was second nature for me to paint and draw.”

“I would call it a constellation,” says Agueznay. “It’s like building another family.”

About Amina Agueznay

Born in 1963, she is the daughter of Malika Agueznay, who is among Morocco’s first female modernist abstract artists and a member of the celebrated Casablanca Art School.

Moving to the US for 15 years after school, Agueznay studied architecture in Washington and practiced there and in New York before returning to Morocco in 1997. She started working on smaller-scale projects, such as jewellery, before expanding to large art installations.

“I returned to Morocco to explore scale in a meaningful way,” Agueznay says. “I can’t hug my buildings, but I can hug my artwork.”

Ksars, fortified villages found across the Maghreb, are made of stone and adobe with palm grove gardens. Some are ruined, but many are being renovated as part of a national push to preserve Morocco’s cultural heritage.

Agueznay was invited to get involved with local people in the project to renovate the Tissekmoudine ksar by the architect and anthropologist Salima Naji, who works on using traditional materials and techniques in such renovations.

Agueznay says she drew a door and asked six women to weave for her. “It’s all a performative process,” she says. “It’s like choreography or ballet for me.”

Amina’s Creative Roots

But Amina’s creative roots reach deeper than just her childhood. In her words, “It is important to understand that in Morocco, everyone is connected to craft and to handmade things. If you want to wear something to a wedding, you buy the fabric and work with the artisan to make a kaftan that is right for you. We appreciate these skills and the relationship between the person who commissions the work and the person who meets those expectations. It is natural.”

It is no surprise then that Amina works in close collaboration with artisans. “When I started making jewellery, I found a silversmith to do the finishing on my pieces. When I couldn’t find all the materials I needed, I created my own matter and brought it to him.”

After returning to Morocco from the US, where she studied and worked as an architect before turning to jewellery design, Amina started facilitating artisan workshops.

behalf of Government agencies where she worked closely with weavers, woodworkers, leatherworkers, basketry weavers and other craft people. She considers all of these influences as catalysts along her way.