The House of Slaves (Maison des Esclaves) and its Door of No Return is a museum and memorial to the victims of the Atlantic slave trade on Gorée Island, 3 km off the coast of the city of Dakar, Senegal. Its museum, which was opened in 1962 and curated until Boubacar Joseph Ndiaye’s death in 2009, is said to memorialize the final exit point of the slaves from Africa. While historians differ on how many African slaves were actually held in this building, as well as the relative importance of Gorée Island as a point on the Atlantic slave trade, visitors from Africa, Europe, and the Americas continue to make it an important place to remember the human toll of African slavery.

From the 15th to the 19th century, Gorée was the largest slaves trading center on the African coast. It was under Portuguese, Dutch, English and French domination. There are buildings of different periods and colonial styles dedicated to housing, education, religion (first mosques and churches) and the slave trade.

Today, about 40% of the island’s buildings belong to the state. On the former military upper part of the island, there are illegally inhabited undergrounds.

The population of Gorée is young, with an average age of 23 years. The real population is estimated at 2,000 inhabitants, 500 of them without rights nor title. The latter are mainly descendants of the former administration employees who continued to occupy the State’s buildings without right nor title. 65% of the population is formally unemployed.

Gorée Island was first visited (1444) by Portuguese sailors under Dinís Dias and occupied in subsequent years. The island’s indigenous Lebu people were later displaced, and fortifications were erected. The town was active in the Atlantic slave trade from 1536 until 1848, when slavery was abolished in Senegal. Historians debate whether Gorée was a major entrepôt for the trade or simply one of many centres from which Africans were taken to the Americas.

This African land mass played an important part in the early days of African history in South, Central and North America. Gorée Island is a small 45-acre island located off the coast of Senegal. Gorée Island was developed as a center of the expanding European slave trade of Black African people, the Middle Passage.

The first record of slave trading there dates back to 1536 and was conducted by the Portuguese, the first Europeans to set foot on the Island in 1444. The house of slaves was built in 1776. Built by the Dutch, it is the last slave house still in Gorée and now serves as a museum. The island is considered a memorial to the Black Diaspora.

An estimated 20 million Africans passed through the Island between the mid-1500s and the mid-1800s. During the African slave trade, Gorée Island was a slave-holding warehouse, an absolute center for the trade of African men, women, and children. Millions of West Africans were taken against their will. These Africans were brought to Gorée Island, sold into slavery, and held in the holding warehouse on the island until they were shipped across the Atlantic Ocean. They were sold in South America, the Caribbean, and North America to create a new world. The living conditions of the slaves on Gorée Island were atrocious.

African Men and Women were chained and shackled. As many as 30 men would sit in an 8-square-foot cell with only a small slit of the window facing outward. Once a day, they were fed and allowed to attend to their needs, but still, the house was overrun with the disease. They were naked except for a piece of cloth around their waists. They were put in a long narrow cell to lie on the floor, one against the other. The children were separated from their mothers. Their mothers were across the courtyard, likely unable to hear their children cry. The rebellious Africans were locked up in an oppressive, small cubicle under the stairs; while seawater was sipped through the holes to ease dehydration.

Above their heads, in the dealer’s apartments, balls and festivities were going on. But even more, poignant and heart-wrenching than the cells and the chains were the small “door of no return” through which every man, woman, and child walked to the slave boat, catching a last glimpse of their homeland.

When the French abolished slavery in 1848, 6000 persons and 5000 former captives lived on the island. Designated by the United Nations Educational, Scientific Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to be a World Heritage Site, Gorée Island in the 21st century retains and preserves all the traces of its terrible past.

The main Slaves’ House built in 1777 remains intact with cells and shackles; the Historical Museum, the Maritime Museum, residential homes, and forts are also standing. The Island today has about 1000 residents.

Gorée, island of memory

A symbol of the tragedy engendered by the transatlantic slave trade, the Senegalese island of Gorée has become a flagship destination for memorial tourism, attracting tens of thousands of visitors every year, including many Afro-descendants from abroad.

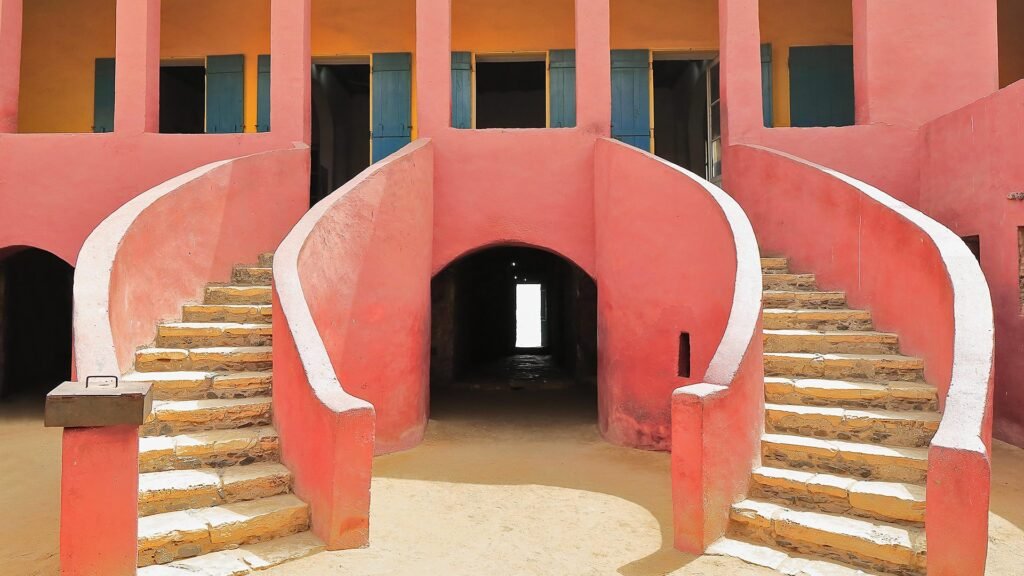

At the foot of the distinctive double flight of stairs in the courtyard of the House of Slaves in Gorée, a guide explains the history of this late 18th century building, used notably as a holding centre for slaves before their forced embarkation for the Americas. Facing him, around fifteen visitors listen in silence while others explore the cells where women, men and children were held captive. “I’m shocked at how small and dark the rooms are into which the slaves were crammed. It breaks my heart to see the conditions imposed on our ancestors,” comments Mohamed, a 14-year-old Senegalese pupil, visiting with his class as part of a school trip.

On the ground floor, at the end of a long, dark corridor, the “Door of No Return” opens directly onto the sea, at the very point where the slaves were taken before their crossing to the West Indies, Brazil, Cuba, the United States or Haiti, among other places. This is one of the most intense moments of the tour. While some people take photos of themselves in front of this emblematic site, others are too overwhelmed by the powerful emotions it arouses.

Olima, a 21-year-old African-American anthropology student, comes away from the visit with tears in her eyes. “It was very intense,” she says. Her friend Gabrielle, a musician-artist from the state of Virginia (United States), is visiting Africa for the first time. “It’s my responsibility to acknowledge and confront the direct or indirect role that my white ancestors played in this trade and to understand the history of slavery,” she explains.

Worldwide recognition

Less than four kilometres off the coast of Dakar, Gorée Island has become the emblem of the transatlantic slave trade. The House of Slaves is the most visited site in Senegal, receiving several hundred visitors every day.

The House of Slaves is the most visited site in Senegal, receiving several hundred visitors every day

This worldwide recognition owes a great deal to the site’s first curator, Boubacar Joseph Ndiaye, who spared no effort to raise awareness of the history of Gorée, even if the central role of the island in the history of the transatlantic slave trade is now debated. Since independence, the Senegalese authorities have been developing safeguarding and promotion policies to make the island a public place of remembrance.

The inscription of the Island of Gorée on UNESCO’s World Heritage List in 1978 marked a turning point. According to the description of the site, “for the universal conscience, this ‘memory island’ is the symbol of the slave trade with its cortege of suffering, tears and death”. Visits by a host of celebrities, including South African President Nelson Mandela, Pope John Paul II and US President Barack Obama, have also contributed to the island’s celebrity.

A place of pilgrimage

“Gorée is at the centre of a veritable pilgrimage celebrating the diaspora of Afro-descendants. The significance and place of the island in the minds of the black diaspora enables us to measure the impact of this community, in search of a lost identity, in the crystallization around Gorée of a memory of the Atlantic slave trade,” explain historians Hamady Bocoum and Bernard Toulier in their book La fabrication du patrimoine: l’exemple de Gorée, published in 2013.

Travel agencies have understood this. “African-Americans who want to retrace the steps of their ancestors make up a large part of our clientele,” explains Mamadou Diagne, Director of the Revina Tours travel agency in Dakar. As a partner of the Harlem Tourism Board, based in New York, he plans to offer his clients a tour of the memorial sites linked to the slave trade in Senegal, Gambia and Ghana.

But foreign tourists are not the only ones to come and pay their respects to the remains of the institutions of slavery. “The development of new means of transport in Dakar has encouraged Senegalese to come. More and more visitors are coming from the African continent in general,” says Kaba Laye, assistant curator of the House of Slaves. In fact, tourism in Senegal has risen sharply in recent years, from 836,000 visitors in 2014 to 1.8 million in 2022.

More and more visitors are coming from the African continent

Several initiatives have been taken over the years to safeguard and enhance the site, but also to attract a growing number of visitors and diversify their itineraries. A revitalization programme, supported by the Senegalese government and the Ford Foundation, has been adopted with the aim of combating coastal erosion and creating a route linking the House of Slaves to the Maison Victoria Albis, which now houses a museum on the slave trade and new forms of slavery. “It is also a centre for the interpretation and documentation of the slave trade. As well as carrying out research, the centre provides training, and we want to create a digital library to archive the work,” explains Kaba Laye.

Since 2017, UNESCO has also been working with local stonemasons on an initial project to restore some of the buildings. A second stage will be launched in 2020 to further develop the site by designing tours tailored to its conservation, and by training guides.

A reference for other memorial sites

The success of the Senegalese island has made it a model for others. “It’s clear that Gorée has influenced other memorial sites that have undertaken the work of remembrance,” observe historians Hamady Bocoum and Bernard Toulier. This is particularly true of Benin and Ghana, which are seeking to develop interest in their own sites of Ouidah and Elmina.

However, there are those who regret that the economic spin-offs are of little benefit to the island’s population. “It’s mainly a question of tourists passing through, staying for a few hours and then leaving again,” laments Lamine Gueye, coordinator of the tourist office.

Over the years, Gorée has established itself not only as a symbol of the tragedy of slavery, but also as a key place for passing on this painful history. However, there are still two major challenges to be faced if this position is to be maintained – the rapid deterioration of certain historic buildings, and erosion, which is inexorably eating away at the island’s coastline.